[go back to Tacelli’s previous argument]

Finite Infinities

Greg Raven

Thank you for your e-mail of July 23.

When I say that infinity is an arbitrarily large number, I mean that it is so large that for example, adding infinity to infinity is meaningless, because each infinity already contains all the elements one could possibly add. Let’s look at what the OED2 CD-ROM says about infinity:

1. The quality or attribute of being infinite or having no limit; boundlessness, illimitableness (esp. as an attribute of Deity).

2. Something that is infinite; infinite extent, amount, duration, etc.; a boundless space or expanse; an endless or unlimited time. (In quot. 1682 the Infinite Being, the Deity.)

3. a. In hyperbolical use (from 1 and 2): Immensity, vastness; an indefinitely great amount or number, an exceeding multitude,

no end(of). [A frequent sense in OF.]3. b. Phr. to infinity (= L. ad or in infinitum): to an

infiniteextent,endlessly,without limit.4. a. Math. Infinite quantity (see infinite A. 4 c): denoted by the symbol <infin>. Also, an infinite number (of something; quot. 1831).

4. b. Geom. Infinite distance, or that portion or region of space which is infinitely distant: usually in phr. at infinity. In Photogr. also used of any distance, or the range of distances, at which an object is effectively in focus when the lens is set for the greatest possible distance.

Using this definition, one can easily gain an appreciation for infinity by examining the use of the word infinity in photography: Once the lens is set an infinity, you cannot make distant objects appear sharper by focussing more on infinity.

Thus, the concept of infinity is arbitrary

to the extent that there is no infinity plus one,

because infinity is already large enough

to contain infinity plus one.

In other words, infinity can’t be defined other than conceptually.

Therefore, even though I do not ascribe to the view that the universe always existed, I must point out that your Kalam-based argument is flawed in that it attempts to assign some fixed number to the concept of infinity. It says, in essence, first that infinity is the number of finite steps through which the universe has gone in the last year to bring us to our current situation. But then it second says that this number

of infinite steps cannot be the same as the number of infinite steps through which the universe has gone to bring us to our current situation for the last millenium, or since 100 trillion BC. You cannot make this statement unless you are attempting to fix infinity with a specific number or size, and because of the nature of infinity, you can’t do that. Put simply, infinity is too big. (There is a second flaw in the Kalam-based argument, which I will address later.)

As for your example of the ticking angel, I think you have conflated two different concepts. While you seem to be attempting to bolster your concept of infinity, you have slipped over into a discussion of the concept of time. Although no one yet knows for certain, it seems that the arrow of time

points only one direction. For what it’s worth, I define time as the measurement of motion.

Stephen Hawking talks about this in his famous book, the title of which I’ve forgotten, but which is something like, A Brief History of Time,

or some such. My view, however, is that once something has moved, there is no way it can unmove,

as both the original movement and the unmovement

are movement, which can be measured and thus which each exist in time; the unmovement

does not negate the movement.

I understand that the Kalam argument is trying to say that the universe must have come from somewhere, because it cannot be infinitely old, therefore it must have come from God. The obvious question is, Where did God come from?

If the answer is that God is not material, not spatio-temporal, then we now have other problems with which to deal. For example, if God is outside of time, how can he be infinite? With no time, there is no way of measuring even finite occurrences, which by my definition cannot occur because their movement implies time. If the universe were created by an eternal non-material agent

(which you define as God), you can no more say what God was doing the instant before he created the universe than the scientists can speculate as to what happened the instant before the Big Bang.

[You are also implying that God gave up his timeless existence to create US — as our creation also would have created time even in an otherwise timeless system — which seems a bit anthropocentric to me.]

Also, and this is a small matter, I reject your attempt to shift the burden of unproof

to me with your statement that my arguments are not very damaging to the Kalam proof that God must exist. Technically, I don’t have to prove that God doesn’t exist, and in fact, it is virtually impossible to prove a negative. It is up to the person making the extraordinary claim — in this case, it is you — to prove his point. Citing the Kalam argument is hardly proof of the existence of an all-powerful, timeless diety.

I realized that the circle and the Koch snowflake were not what I would call true infinities. I presented them, in that specific order, so as to ease us into an understanding of what we are up against in dealing with infinity.

This gets us to what I referred to earlier as the second flaw in the Kalam argument. One of the corrolaries of the Kalam argument is that infinity is impossible because there is no end to it. I dealt with this in my first rebuttal on the nature of infinity, but we don’t even have to go that far to see a potential fallacy in the logic of the Kalam argument. You stated:

Can an infinite task ever be done or completed? If in order to reach a certain end, infinitely many steps had to precede it, could the end ever be reached? Of course not — not even in an infinite time. For an infinite time would be unending, just as the steps would be. In other words, no end would ever be reached. The task would — could — never be completed.

But what about a sufficiently large FINITE task?

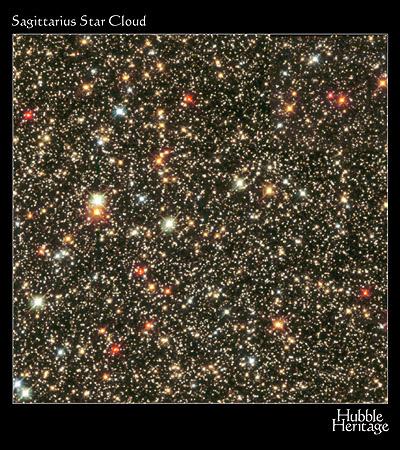

There are roughly 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (10 to the 24th power) atoms per cubic centimeter of matter. The sun’s mass is roughly 2 billion billion billion tons, which is about average for known stars. Normal galaxies, such as our own Milky Way galaxy, have between 1 million and 10 trillion solar masses. The Milky Way galaxy is just one of billions of galaxies known or thought to exist, plus there are planets, comets, dust, asteroids, moons, dark matter, etc.

This photo was created with support to Space Telescope Science Institute, operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., from NASA contract NAS5-26555, and is reproduced with permission from AURA/STScI.

All of this makes up some large, but presumably finite, number of atoms. Question: Can you count the number of atoms in the known universe?

I’ll bet you can’t, but not because I believe the universe is infinite. The problem is not one of infinities, but of our ability, as finite beings, to comprehend even large finite constructs, let alone a potentially infinite construct. In my first rebuttal I cited this as the main failing of the Kalam argument.

This photo was created with support to Space Telescope Science Institute, operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., from NASA contract NAS5-26555, and is reproduced with permission from AURA/STScI.

The Mandelbrot curve does only represent a portion of its view of infinity at any given time, but that does not mean it is not infinite. When you look up at the night sky, you see only a portion of that sky. In fact, it is impossible to see any more than a relatively tiny portion of that sky which is visible to the naked eye. This doesn’t mean that the universe isn’t infinite. But we as humans are not able to observe infinity, no matter how it manifests itself. We must be content with frozen moments, or pieces of infinity. The Mandelbrot curve is valuable if for no other reason than for helping to illustrate this reality: If you want to look at more infinity

using the Mandelbrot curve, plug in different variables. One is tempted to say that given enough time, one could plug in an infinite number of different variables.

Therefore, not only is infinity

a mathmatical concept that may not have any corrolary in reality, but we as human beings are thus far incapable of comprehensively dealing with even modestly large finite sets, let alone infinities. Given this, why draw the line at infinity when attempting to demonstrate the existence of God? Why not select some sufficiently large finite number as the human limit, ascribing to God everything beyond that limit? For practical purposes, the end result is the same, although without the straw man of a misdefined infinity to attack, the Kalam argument loses its veneer of philosophical sophistication and descends to the level of superstitious mumbo-jumbo.

Finally, you say that for the universe to be brought into existence, there must have been more than the potential for it to exist, there must have been something actual. I think you misunderstood my point. If you have cement, sand, aggregate, water, some tools, and someone to mix the components together, you have the potential to make concrete. These are actual items, but if they are not combined, you won’t have any concrete.

Similarly, I believe that all we can say about the creation of the universe is that there must have been the potential for it to be created, although I have no idea what the actual nature of that potential might have been. It might have been God, a big bang

from an unimagineably small singularity,

a tear in the space-time continuum that allowed a universe-worth of material to pour out from some alternate form of existence, or it could have simply always been whirling around in space.

Up until now, however, your arguments seemed to be that God is (or at least, was) outside the spatio-temporal realm, that is, he could not be said to exist, at least by our definition of existence. Now, you seem to be saying that God existed to the point that he was actual.

That is, that he was quantifiable in some way, shape, or form. If that is so, then he was NOT outside the realm of time, and because he can be said to have existed, faces the same problems with origin that you decry in the secular version of the origin of the universe.

read Tacelli’s response